Hardly Lost: Ukraine’s young adults choose purpose amid travesty of war

By Les Beley, CNEWA

University student Daria Bazylevych was at home in Lviv, western Ukraine — 560 miles from the front — when a Russian missile struck her home on 4 September, killing her, her mother and two sisters.

Within weeks, Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU), where she was enrolled, created an endowed scholarship in their memory.

Daria is among the growing list of members of the UCU community who have been killed in Russia’s nearly three year-war on Ukraine. As of 30 September, 31 students, alumni and staff had been killed as active military. Another 130 were serving in the Ukrainian army; numerous others were assisting with humanitarian aid efforts across the country.

UCU operates a veterans center that collects aid and assists veterans with re-entry into civilian life. Pavlo Koval, the center’s director, notes all veterans face many similar social and personal challenges. However, the common request among young veterans who joined the military without completing their education is to study and build a career.

Dr. Oleh Romanchuk, a psychiatrist and director of the university’s Institute of Mental Health, says Ukraine’s current young adults, aged 18-25, faced an onslaught of challenges before even reaching adulthood.

“First, they experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, and now they are going through a full-scale war,” he says. “During their youth, everyone wants to envision their future and pave the way toward it. But that future is shrouded in uncertainty, because no one knows how long the war will last.”

Dr. Romanchuk says the constant stress of war, massive shelling, power outages, and the loss of homes and loved ones have resulted in a common list of mental health issues among this population, namely anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep disorders and eating disorders.

However, the psychiatrist says it would be wrong to consider this generation to be “lost.”

“They are already hardened by the war. We see an incredibly strong civic stance, massive involvement in volunteer work and resilience,” he says. “Despite all the challenges, they continue to pursue education and firmly state they are only young once and do not intend to start living only after the war.”

While these young adults have been deprived of carefree days, he says, and many have attended more funerals than weddings typical at this age, there is also a widespread phenomenon of post-traumatic growth toward greater resilience, humanity and purpose.

Ukraine’s 18- to 25-year-olds are a relatively small group. The economic crisis during the restructuring of the country’s post-Soviet economy in the late 1990s and early 2000s discouraged young couples at the time from having children.

According to the World Bank, the birth rate in Ukraine in 2001 was 1.1 births per woman — the lowest in the 31 years between Ukrainian independence and the current war. As a result, 3.1 million people in this age group were living in Ukraine in January 2022 compared with 5.5 million people aged 35-42, according to the State Statistics Service.

Uncontrolled mass migration at the start of the war and the ongoing loss of life makes the current size of the 18-25 age group within the country — as well among the 6.5 million Ukrainian refugees worldwide — indeterminable. However, about 350,000 people aged 18-25 are estimated to be among the 3.7 million internally displaced, according to the International Organization for Migration. By 1 October, no casualty data specific for this age group was available, although total civilian deaths had exceeded 11,500, and military deaths were believed to have exceeded 31,000 — the latest official figure for Ukrainian military deaths reported by the president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, in February.

Ukraine has had a general mobilization since the start of the full-scale war, initially for men aged 27-60. In April, the conscription age was dropped to 25. However, men and women under 25 have been volunteering for the military since the war began.

While the number of these recruits is classified information, the average age of Ukraine’s roughly one million active military ranges between 40 and 45, says Serhiy Rakhmanin, a member of parliament on the National Security, Defense and Intelligence Committee.

Vasyl Dzesa, a recruiter for the 24th Mechanized Brigade, based in Yavoriv, Lviv Oblast, says recruits under age 25 are usually motivated by a desire to avenge loved ones killed in the war. Their admission is not automatic, he says. His reflex is to send them away and advise them to reflect further on their decision. Some reconsider, while others return, taking on combat roles as soldiers, drone operators and medics.

Volodymyr Shypitsyn, motivated by honor and the pursuit of justice, was 19 and studying law at UCU when he enlisted. After completing his military training, he carried out combat missions in Donetsk Oblast, eastern Ukraine.

Uninterested in military desk work after an injury in battle last year rendered him unfit to return to the front, he demobilized. He says he was spared any severe psychological consequences he had expected from serving in battle and has restarted his university studies, this time in international relations.

“The war prompted me to study the reasons behind the war’s occurrence,” says Mr. Shypitsyn.

“I want to be a specialist who brings maximum benefit to post-war Ukraine, helping to build a new image,” he says, “not as a place of destruction and sorrow from which people flee, but as a place of great opportunities.”

Not all young men return to civilian life after combat. A Ukrainian soldier with the call sign Sabotage says he knows nothing aside from the war.

Sabotage, 20, was studying to become a feldsher in his home region of Sumy Oblast, northeast Ukraine, when it fell under Russian occupation in 2022. He decided to enlist after witnessing various war crimes by Russian soldiers.

“I realized that I am a man. I have arms and legs, I am healthy. Why should someone else die for me? The last straw was when a good friend of mine died in the war,” he recalls.

He told his mother he was leaving to work as a security guard on the railway, then joined the 3rd Assault Brigade, based in Kyiv, 186 miles away. The brigade is among the most popular with young volunteers due to its reputation for excellent training — and, in part, to its strategic YouTube and billboard advertising campaigns.

His mother only learned later he had joined the military from a TikTok, in which her son, concussed, was lying under a tree.

Sabotage spent two months on the front near Avdiivka, Donetsk Oblast, sustaining two heavy concussions. The second occurred in March 2024, when an artillery shell exploded nearby. He recovered. However, no longer suited for battle, Sabotage became an instructor at his brigade’s training base in central Ukraine.

“Younger recruits are more motivated and always eager to fight,” he says. “Older people think more about their families, while young guys don’t have that.”

Sabotage, who used to be timid, says he has found true friends in the army and has lost his sense of fear. He is satisfied in his new role, as he had always dreamed of becoming an instructor.

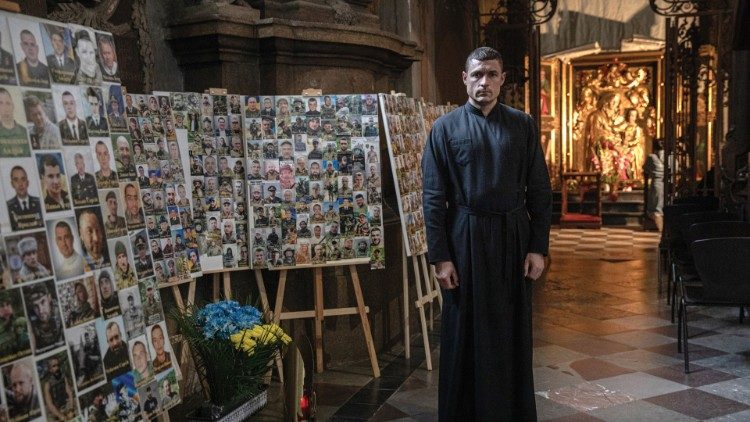

The Reverend Andriy Khomyshyn, an UCU graduate, has been providing spiritual support to Ukrainian soldiers since 2008. He serves as chaplain at the Hetman Petro Sahaidachny National Army Academy in Lviv, where officers are trained.

Before the war, young people were widely considered to be “unreliable and indifferent” to the political events in the country, he says.

“But they have shown they were underestimated,” he says. “They have a strong desire and readiness to shape their own future. They understand they can only rely on their own knowledge and skills, and they have a completely different understanding of authority.”

Young people are not impressed by status or rank, he explains. They judge people by their actions, they are prepared to question everything they are told and are irritated by empty slogans. Bridging the gap between generations is challenging, he adds.

In addition to providing sacraments and other spiritual care, listening to the young soldiers’ experiences in battle has become an important part of his ministry. He recalls a few of the difficult stories he has heard: a soldier who talked at a corpse for two hours when there was no one else in the trench to speak to; another soldier who feared killing had become “easy” for him after battling enemy forces in Bakhmut; and yet another who was recovering from a gunshot wound to the head.

“I realized these young people carry such a tremendous burden that, when they decide to share it, not every civilian will be able to handle it,” he says. “We will have to establish a public dialogue after the war, not only between different generations but also between those who have gone through the war and those who have not been as deeply affected by it.”

Kateryna Kremin had dreamed of becoming a teacher, but the war moved her to pursue a different path.

This past summer, Ms. Kremin volunteered nearly full time, helping children with special needs at a center in Ternopil, 70 miles east of Lviv, run by Caritas Ukraine, the charity of the Greek Catholic community in Ukraine.

When university resumed in the autumn, Ms. Kremin turned her focus to logopedics, or speech-language pathology, which helps children and adults with neurological damage to develop or regain speech.

“Many of my friends have chosen professions related to supporting the military — psychologists, medics,” says the 19-year-old. “I have two cousins serving [in the military], and it’s hard. I understand they will need professional help.”

Volunteerism in the country has increased since the war began, especially among young adults. Volunteer coordinator at Caritas Ternopil Natalia Protsyk says her team of seven volunteers before the war grew to about 100 in 2022. Of her 35 volunteers in mid-September, 20 were young adults. She says young volunteers are “full of energy, and creative ideas, so they contribute a lot.”

“They have the possibility to see how people in need are living and they have much commitment and empathy,” she adds.

Lidia Hnatiuk, 21, a finance student in 2022, was among the volunteers to join Caritas Ternopil. Inspired by its mission, she decided to pursue a career in social work instead. She has been working as a case manager with Caritas for the past two years, assisting vulnerable people with documentation, access to medical care, housing and employment.

On 17 September, Ms. Hnatiuk and her colleagues welcomed an evacuation train from Donbas, eastern Ukraine. The 65 passengers — adults, children, elderly and some with special needs — came with modest packages of belongings and their pets. Caritas staff greeted them on the platform, showing genuine care. About two evacuation trains arrived in Ternopil each week in September.

Ms. Hnatiuk says it was difficult initially not to take on others’ pain, but she learned how to maintain professional boundaries and still show empathy thanks to the training she received at Caritas.

“Under the influence of war, I have matured,” she adds. “I have begun to notice how many people need help.”

Maria Khudiakova, 22, lives in Brody, about 42 miles northwest of Ternopil. Her hometown in southern Ukraine, Oleshky, in Kherson Oblast, was occupied by Russian forces on the first day of the full-scale invasion. During the occupation, she volunteered to stand in various lines on behalf of elderly people to buy them food and deliver it to their homes.

When she fled Oleshky alone in mid-April 2022, she believed the war would soon end and she would return. However, in June 2023, 80 percent of the city flooded after an explosion at the Kakhovka hydroelectric station. The number of casualties has gone unreported, and power still has not been restored to the city that remains under Russian occupation.

Her new life in Brody was not without its challenges.

“In the first month, I was extremely withdrawn,” she says. “I had hallucinations: I could walk down the street and see a shot-up car with the Russian symbol ‘Z’ or, in the complete silence, I could hear explosions in my mind.”

Ms. Khudiakova, who is a remote student in music at Luhansk State Academy of Culture, says volunteering with teenagers at the local Caritas center helps her cope with her trauma.

Once a month, she and her husband, Fedir Khudiakov, 25, also volunteer to drive their van full of humanitarian aid they collect at their Baptist church to the combat zone in Donetsk Oblast. They have come under shelling on their runs to the front, but they say their desire to help outweighs their fear.

The couple met in Brody in 2022. Mr. Khudiakov, originally from Pavlohrad, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, in southeastern Ukraine, also fled alone to Brody, where he works at a factory that manufactures replacement parts.

While the war has taught the couple not to make too many long-term plans, they married on 22 September and honeymooned in the Carpathian Mountains in western Ukraine. They decided to build their life in Brody, where they have rented an apartment.

“We decided to get married because life goes on,” says Ms. Khudiakova. “We have to live in the circumstances we have.”

“As for children, I believe everything is in God’s hands,” she adds. “There’s no point in waiting for the war to end because it’s unclear when it will be over.”

With the possibility of conscription ahead, Mr. Khudiakov says he is ready to serve on the front as a chaplain, given his religious commitment to pacifism.

“I wanted to serve this way, but there are no vacant positions at the moment,” he says.

In Zakarpattia Oblast, western Ukraine, Oleksandr Smereka, 19, has chosen the path for the priesthood. He was in his last year of high school when Russia began its full-scale invasion. When classes were suspended and later moved online, he joined the humanitarian efforts of the Greek Catholic church in his hometown of Khust.

“I met many people from different parts of our country, listened to their stories,” he says. “I was pleased I could help these people.”

Later that year, he began his studies at Theodore Romzha Theological Academy, the seminary of the Greek Catholic Eparchy of Mukachevo in Uzhorod.

Mr. Smereka says he first felt the call to the priesthood at the age of 8, when he was preparing for first Communion. He decided to pursue the call in his teenage years.

Three years into the war, Greek Catholic priests in Uzhorod continue to deliver humanitarian aid to the front line, and Mr. Smereka and other seminarians help sort and pack the aid.

“I want to finish my studies, be ordained, maybe serve in a parish and, if needed, become a chaplain,” says Mr. Smereka.

“I don’t know what the future holds for me. I think only about today. Everything else is in God’s hands.”

This article was originally published in ONE, the magazine of Catholic Near East Welfare Association (CNEWA). All rights reserved. Unauthorized republication by third parties is not permitted.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here